Today I want to share an interesting challenge that’s been bugging me since I joined InvestSuite last December. It’s stories like this that makes me happy to be a developer, being able to address things that are ruining my day and get rid of them. It feels so satisfying.

We work with massive JSON files (deeply nested, sprawling structures), and we needed a way to test them reliably. The stability of StoryTeller, our personalized report engine, depended on it.

Let me give you some context first.

How StoryTeller works

Our tool, simply said, generates hyper-personalized financial reports. Every word in them is tailored, whether it’s referencing a customer’s name or how their portfolio performed in the past months.

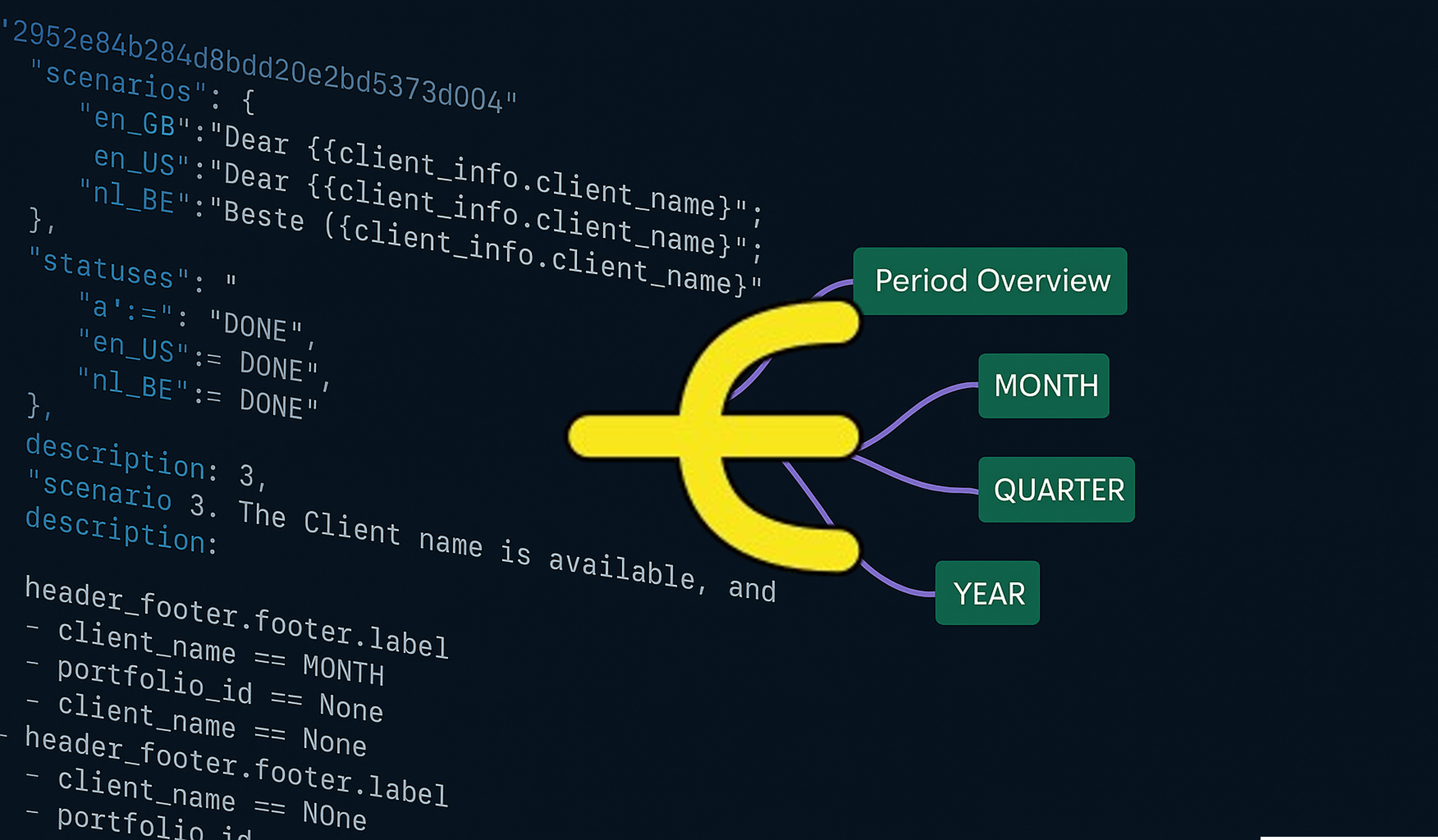

In the most “rigid” version of StoryTeller, we define a logic tree to compose each sentence. Think of it like a massive if-else chain: dozens of nested conditions that cover every possible scenario. For each one, we have pre-approved text to use in the final report.

For example here, each section is built based on several factors. The first 3 words This excellent quarter depends on the portfolio’s performance (very good) and the reporting period type (quarter).

Why so strict? Compliance. Every line that may appear in the report must be approved in advance by customer’s legal team. That means we need a full database of all possible variations, and the logic to match each one correctly.

Here’s the catch: This tree has to cover EVERYTHING.

A portfolio can go up, down, or stay flat. A quarter can be Q1, Q2, Q3, or Q4. Every combination matters, and conditions often reference each other, so the number of possibilities explodes in the more advanced parts of the report. Miss just one, and Storyteller will crash because there’s no corresponding text. We call this a missing scenario and it was my worst nightmare.

When the logic file grows to 100k lines with 12+ intertwined conditions, it’s painfully easy to miss something obscure. Maybe a combo that never happens, until it does, and weeks later you’re frantically searching for that missing scenario to fix it on the fly.

My struggles

From day one, I was thinking: how do we make this system more stable? It was driving me insane.

Back then, the text database was responsible for ~70% of our bugs. A customer tested a bunch of reports, and many of them crashed because of missing text scenarios. I spent days navigating these giant files. They are so big that not even Gitlab diff view are displaying the changes between versions, you need to scroll through each JSON line and write down the scenarios and find what’s missing. My eyes were burning.

Yes, 75k, sometimes even 100k+ lines. Imagine scrolling through that monster of a JSON file, hunting for a single missing piece.

Also, the logic of the text database was not always clear to developers, because it was implemented by copywriters who know how to tell “the story” and are creating the scenarios.

We never had the certainty that everything was covered. We had already implemented a bunch of stability patches, but testing these trees was still a nightmare. Or was it?

First idea: brute-force it

My first idea was to just try all the scenarios. Loop through every combo of inputs and let the tool crash if something’s missing. Makes sense, right?

So I created a script that isolates that part of the code, loads a random value for each conditions (e.g. a performance can be >0, 0 or <0, a quarter can be Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, etc…) and tries every single combination.

Problem: it doesn’t scale. The combinations grow exponentially: hundreds of millions of possibilities. Each test might be fast, but running all of them was not feasible.

Not going to share my terrible code here 😇

Then my PM said something that shifted my thinking. We don’t need to run every case: we just need to see the logic clearly enough to spot problems.

Second idea: use Miro to easily visualize the tree

That was the insight. Our copywriters already use whiteboard tools like Miro to brainstorm logic trees visually.

So why not just bring that into our testing process? If we can compare the visual tree with the JSON structure, we could catch inconsistencies before they break production.

With a mind map (like Miro), you can spot missing branches easily. You can collapse nodes, focus on one part of the tree, and review logic visually. It’s not perfect, and human errors can still happen, but it makes everything reviewable. You isolate the problem from thousands of JSON lines to a simpler graph, way more manageable, even for non-technical people.

So I gave it a shot. I set up a Miro project, wrote a script to export their mind maps in a JSON-compatible format using their API, and added some lightweight tests. It was quite fun: I re-created the scenarios as nodes in Miro, ran the script, and the tool was comparing expectation, suggesting missing cases, and even highlight similar-looking logic paths.

It worked great for a prototype. But once the node count grew, Miro became unusable and slow, and the experience worsened.

My biggest problems is that the search and replace feature hanged, making it unusable (we have dozens of trees, one for each part of the element) and when I had to create a new one there was no smart copy-paste (either grab a whole tree or nothing).

I started using several Miro files to be able to open them but this was getting out of hand. And as a third-party tool, it didn’t fit well into our version control workflow.

Miro didn’t even try to load that many trees and this was just a tiny slice of the project.

It wasn’t production-ready. But I was in the right direction: I was easily spotting missing scenarios thanks to the mind map structure and we started fixing bugs!

Third idea: mind maps with markdown

That’s when I stumbled on Markmap: a tool that turns simple Markdown files into interactive mind maps. You install a VS Code plugin, click the extension button and the file becomes a clickable, zoomable, collapsible tree very similar to Miro.

It was exactly what we needed.

I could finally keep the structure in version control. I could diff changes properly. And more importantly, I could build and review logic trees without ever leaving my editor.

The beauty of Markmap is that it’s ridiculously simple:

You write nested headings in a .md file:

- Title

- quarter == Q1

- performance > 0

- performance < 0

- performance == 0

- etc...

…and voilà, you get a mind map. It’s clean, minimal, and fast, even with hundreds of nodes.

Each tree has its own file, which you can quickly open for reviewing (we usually audit 1 part of the report only)

This solved so many issues at once:

- Version control: Trees now live in our repo, reviewed and updated like any other piece of code

- Performance: Markmap scales well, wit no lag even with thousands of nodes

- Searchability: Finally, we can search, grep, and diff logic trees just like any other text file

- Collaboration: Since it’s Markdown, our copywriters could pick it up easily

It also unlocked a smarter workflow: Now, when the copywriter proposes a new scenario, we update the Markdown tree first. Tests are synced directly from it. If something breaks, we get a precise error pointing at the missing or invalid node. The mental model shifted from “fixing JSON bugs” to “keeping the logic tree healthy” and that’s a much better place to be.

Example of a complex tree originally spanning 5,000 JSON lines, reduced to just 100 in Markdown.

This simple change also created a shared understanding between developers and content writers. Before, logic lived inside JSON blobs that only devs could parse. Now it’s visible, editable and reviewable by the whole team.

And we can finally enjoy smoothless report runs with zero missign scenario errors (which, I remember you, represented the majority of our bugs), because all the combinations have been reviewed to ensure there is always text for each case.

It took some trial and error, some learning, but now StoryTeller is more stable than ever. And I don’t need to review these huge JSON so frequently anymore. This is what makes me love what I do: building and creating tools to solve boring tasks.